JUMP JIM JOE

October 30, 2019

by Andrew Ellingsen

At last year’s Alliance for Active Music Making symposium held at the American Orff Schulwerk Association conference, Dr. Jacqueline Kelly-McHale shared her research on the song “Jump Jim Joe.” This song was one that I taught early in my teaching career, but at some point, I learned that a previous iteration of the song had been “Jump Jim Crow” -- knowing that the song grew directly out of the racist laws and policies that followed the American Civil War, I stopped teaching the song.

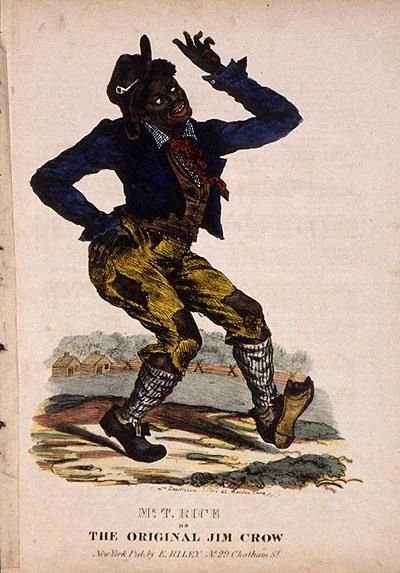

Briefly, “Jump Jim Crow” was made famous by a white minstrel show performer named Thomas Dartmouth Rice in the 1820s. It was a huge hit, and was performed in minstrel shows across the country. At some point, “Crow” became “Joe,”and the peppy tune made its way into the collection of songs taught in countless elementary schools in our country.

Hearing Dr. Kelly McHale share the full history of the song (as well as a host of insightful, eye-opening, and thought-proposing ideas) was helpful to clarify my thoughts around what should and should not be included in a music classroom. Rather than reiterate her points, I’d like to steer you directly to her article from the March 2018 issue of the Music Educators Journal titled “Equity in Music Education: Exclusionary Practices in Music Education.” (Not a member of NAfME? There is likely a college or university near you with a subscription -- a quick visit to their library would allow you to read the article in full!)

The article is short but incredible. My favorite quote from the article is one that is now a basic tenet of choosing repertoire for my classroom.

When we teach music, we teach a subject that incorporates cultural, social, and expressive elements. A song carries with it the history of the person who wrote it or transmitted it. A song provides a window into the past, whether that be an angst-filled

love song, an angry call for change, or a song that tells of a historical conflict. If we want to categorize something as part of a canon, then we must justify its inclusion based on the entirety of the song and not exclude aspects that may be difficult to address or based on our ignorance; otherwise, we become complicit.

There is much I don’t know. I had incredible training in music and music education in the public school and in my undergraduate and graduate courses...but there is much I don’t know. In the words of Maya Angelou, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

We have access to a host of information that music educators couldn’t get prior to the internet. A quick Google search of most folk song titles will turn up enough information to tell if there are obvious red flags. And if there are? Well, then we know better. And we must do better.

(Side note: The New York Times 1619 Project is incredible -- they’re doing a really powerful job of telling stories that have been ignored. The third episode of the podcast produced as part of the project tells the history of American music and specifically includes more information about the role of minstrel shows in America.)

FURTHER READING:

“Equity in Music Education: Exclusionary Practices in Music Education,” Dr. Jacqueline Kelly-McHale. Music Educators Journal, March 2018, Volume 104, Issue 3, pgs. 60-62.

More information about the lyrics of “Jump Jim Crow” from the Bluegrass Messengers and from Black Past.

A dialogue on blackface minstrelsy from the PBS series American Experience.

Music educator Josie Holford shared her thought process for dropping the song from her curriculum in her blog post “Beneath the Surface: The Hokey-Pokey and Jump Jim Joe,” from October 13, 2012 on the blog Josie Holford: Rattlebag and Rhubarb.