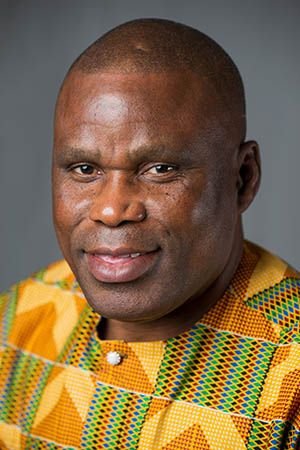

AN INTERVIEW WITH DR. KOFI GBOLONYO

January 19, 2021

by Brandi Waller-Pace

In the summer of 2019, not long after starting DTMR, I participated in a week-long Orff Schulwerk masterclass given by la Asociación Orff España in El Escorial, Spain. The experience opened my eyes to the way this approach that I had frequent interaction with in the context of the U.S. educational system functioned in a totally different country. I was privileged to have Dr. Kofi Gbolonyo as one of my teachers for the masterclass.

The way he spoke to music making, understanding full context, and systemic issues in how music from the continent of Africa is used among Western educators made his classes even more powerful for me. He was kind enough to sit down for an interview and talk about his musical experiences within his own culture in Ghana and the academy, the effects of colonialism on the musical traditions of his country, and important things we should consider when engaging with music from his and other African cultures.

Brandi Waller-Pace: Can you please start by introducing yourself in terms of both your cultural identity and your work?

Kofi Gbolonyo: My name is Kofi Gbolonyo. I am a professor of ethnomusicology and African studies and I am from Ghana and an Ewe by ethnicity. I am a musician, professor, music educator…anything that has to do with music and culture.

BWP: Our class has had discussions about the function of traditional music in different cultures. Can you tell me about your musical experiences growing up, and the functions of music in your culture?

KG: Well, I grew up in my country, my ethnic group, my hometown–you have music all around you every day, from birth. So, you don’t necessarily take a music class, but you imbibe music on a daily basis, depending on how much you get involved in activities including children’s games, community music making, both by adults, children, youth and mixed ages. So that’s pretty much my musical exposure, in terms of traditional music. But I also was raised as a Christian, so one part of me is still traditional, and one part of me was in school and raised as a Christian–as a Catholic. So, through that I was exposed to Western music, both in the church and also in the school system. Because the schools were built by German and British missionaries and colonial masters, that’s how we got access to Western music. Basically, initially through Western wind instruments, brass instruments–brass are very common in my part of Ghana. So that’s how we got exposed to Western music. So, I first started playing trombone, which has remained my major Western instrument. So those are my two musical exposures: one traditional and one Western. Traditional from birth, and Western we started getting exposure to as soon as we started Western education.

BWP: In terms of your admission to university, what do you feel granted you the most access as far as the type of music you made? Did you feel like you had to lean more toward the trombone?

KG: Well, we follow the typical Western curriculum, the music curriculum–which is completely based on the British system. So, for you to enter college and to read music you have to pass all the exams that somebody in America or in Britain would have to pass. So, it’s pretty much Western music–it’s everything you do in America or everything that is done in Europe. So, your traditional music aspect is something you get from home, from everyday involvement in your traditional activities. But later on in the university, yeah, there are traditional music areas that are taught. But if you rely on that only– learning it from the colleges and the universities – you’re not going to get much from traditional music.

BWP: How has colonialism affected the teaching and presentation of music in your culture?

KG: Well if you are talking traditional music--

BWP: Traditional music specifically.

KG: Well, traditional music–colonialism tried to completely eradicate it when the missionaries were there, when the colonial masters were there. But they did not completely eradicate it, so there evolved two streams of musicians: one, those who were converted into Christianity were completely prevented from participating in traditional music. And so, they continued on the European, missionary, Christianized path of music. And those who were not converted actually held on strongly to the traditional music.

So the effect of it was that…[intentional distancing from] colonialism somehow partly aided the preservation of traditional music–in the sense that those that were not converted into Christianity continued purely on traditional means and methods and grounds. And those who were converted–while they were being forced to take and to absorb the Western musical traditions, they did not 100% absorb the Western musical tradition. They still had the element of traditional music that they brought into the church, into the schools. So, hybridization started from that and from there.

While hybridization of Western music continued in Africa, traditional music in many parts–particularly talking of West Africa, in particular in Ghana–continued unaltered. Because those who were not converted to Christianity had nothing to do with Western music. Therefore, [Western music] had no influence, did not bring any influence on traditional music that they were playing. You get my point? So the new forms of music that came to be, came to be as a result of the transformations and amalgamation that happened in the church and in the schools–not in the traditional setting, because those in the traditional musical setting were not converted and therefore not allowed–they had nothing to do with Christianity, they had nothing to do with westernization in terms of musical cultural influences.

But those who were converted were forced to have access to Western ideas of music and resources, and absorbed those ideas to a point, but they could not completely shed away the traditional musical element.

BWP: What were the religious practices of those who were not converted?

KG: There were so many traditional religious institutions–very many–because our cultures permit a multiplicity of religion. Religious tolerance is very high. So, an individual is permitted–is allowed to practice as many religions as one wants to. But Christianity and Islam did not allow that. So, you are a traditional musician in traditional religious music and you got converted to Christianity, you are forced to focus on Christianity and Christian music. But if you are not converted you continue to practice traditional music and play for the various traditional deities including the God of Thunder and Lightning; you may also play for the God of the Sea if you are a devotee of that deity; you may play for the God of Fertility and you can also play for the God of War–because you believe in or are a devotee of one or all of those deities and you can be a member of those religions, a devotee of all those deities/divinities. But when you become a Christian, you have to be only for Jesus Christ, and nothing else.

BWP: What are your general views of Western academia and music education and its part in how music of your and other African cultures has been spread through the Western world?

KG: My views on that are not any different from my views on colonialism, missionary works, and westernization in Africa, because Western institutions form part of the colonial system. So, in part, Western institutions initially started as a way of looking at African music and cultures as coming from an ‘inferior’ race, so it was treated as such.

For example, the creation of the commercial musical category called “World Music” and the academic classification of Indigenous African music under World Music–which does not include Western music; the creation of the academic discipline “ethnomusicology” and the categorization of African music under ethnomusicology, etc. Those are direct or indirect colonial perceptions and demarcations that Western institutions have brought onto the study and dissemination of traditional music.

But things have changed since then–or things are changing– so that now we have a few Indigenous voices who are looking at traditional music and music from these cultures from their Indigenous perspectives. So now I go and I talk about my music from my perspective–from the Ewe perspective–from the Ghanaian, from the West African perspective. Which is adding that other voice, other than the one that the institutions started with. Westerners were, Western institutions were only looking at African traditional music from a Western perspective, which has initially brought in some wrong approaches, misunderstandings, and misconceptions.

So, Western institutions in my view have played both roles–have played negative roles in terms of the misrepresentation and presentation of African music, but at the same time have also played some positive roles. For example, we African musicians are indigenously not into transcription and notation of African music. But to face it, if Africans really want to package the music–the traditional music–and put it on the world stage we have to find a way to understand the world musical language, which includes Western notation and transcription and all those things, although it’s not going to be perfect. Western notations and transcription are not perfect, but they will definitely help you, the teacher. Even if you are presenting that from your ethnic perspective, your insider’s perspective, those tools will still be useful tools for you–which are tools provided by Western institutions.

BWP: So, what are some of the things you find most problematic in terms of publishing and resources that are provided to teachers, particularly primary teachers?

KG: One: lack of deep research. Two: lack of respect from the people who want to publish materials from traditional African cultures. And three: just people being in a hurry to publish, to publish, to publish–so many have ended up publishing things that they know very little about. Because they heard a song from this one guy, who might just know the melody but might not even know the context in which that song is performed. Or knows the context, but can just not explain the context and the function of the music–sings to you a very nice melody, and then you go and you publish it.

So there are issues like the source of the material published. Think of a continent, a country, an ethnic group, a town, a language, all of those things. And so people publish and say, “this is an African traditional song,” or “African traditional children’s game” and all of those things. That is nonsense…you write “African children’s game”–and one may ask, “Which part of Africa? Which Region, West Africa? Central Africa? Southern Africa?” or “Which country? Nigeria? Ethiopia? Kenya? Ghana?” Or “Which ethnic group?” When we know Africa has over 2000 ethnic groups, over 2000 languages, etc.

So, if you really are publishing that as a good educational resource, you should be able to do a better job, do better research to be able to answer those questions before publishing. So, there are many songs and games and pieces that have been published that are questionable and that lack basic information and have serious issues with them. And that, for me, is just setting the tone for the crucifixion of those resources in those cases.

BWP: So as teachers–personally, I am primarily an elementary music teacher–what do you feel like are the most useful things I can do, knowing there are so many cultures and ethnicities? What are my best access points to make sure I’m teaching musical traditions properly?

KG: First you have to ask yourself, “Why do I want to teach this song? Why particularly a song from Africa?” If you are able to answer those two questions, then immediately you know what you have to do. If your aim is to teach about Ghana, truly teaching a song from Ghana, then you’ve got to do/learn more about Ghana. In that case, you have to know that Ghana is made up of over 50 ethnic groups and languages. And so if you want your children to learn this song and know that there are over 50 ethnic groups and languages; then you have to know that this song comes from one of those ethnic groups, uses one of those languages; a particular language and by a particular ethnic group. And you have to make sure the song you are teaching–you know which ethnic group it comes from, which language it’s sung in; don’t just teach the song or learn the song like: “This is a song from West Africa,” or “This is a song from Ghana.” Be able to answer those questions. But if your answer to those questions is just, “This is a cool melody,” then just don’t teach it. If you end up teaching the song [anyway], and the children ask you, “Where is that song from?” You are going to answer them “An African song”. Period.

So as a teacher, you’ve got to do your homework. You heard a melody, you’ve seen something published, you see something on the internet–there is more available and more access these days. Gone were the days when we could count [the number of] Africans who [are] in music education who are outside of Africa. Today you don’t have to go to Africa to be able to communicate with ten Africans in a day. There are many ways you can find out, “Where is the song from?”

This author says, “it’s an African song, a traditional song.”

“What are the languages?”

Okay? There is a lot you can do.

You see somebody who says, “I’m from Nigeria.”

“Oh! I heard this song is from Nigeria. Do you know it?”

“No, I don’t know it.”

“Why?”

“Because in Nigeria, we have 300 languages.”

Does the word sound like a word in one of the languages you know?

“Oh, I think this word sounds like Hausa.”

“Do you know any Hausa speakers?”

“Yes, I know that guy who lives there.”

“Oh, I have this friend from the Hausa area of Nigeria, you can email him.”

There are so many ways you can find out about things. Don’t tell me it consumes time. It’s the knowledge you want to preserve, so you have to make sure you are preserving what is worth preserving.

Dr. Kofi Gbolonyo is a Sessional Professor of Music and African at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, where he teaches courses in African music, Ethnomusicology, and African Studies and directs the UBC AfricanMusic Ensemble. Professor Gbolonyo is also the Founder and Director of Nunya Music Academy and the Orff-Afrique International Professional Development Programs in Ghana. Professor Gbolonyo holds a Ph.D. and MA in Ethnomusicology and a Graduate Certificate in African Studies from the University of Pittsburgh; a Certificate in Orff-Schulwerk Level III (San Francisco Orff Course); a BA Honors in Linguistics and Music from the University of Ghana; and a Teachers’ Diploma in Music Education and Ewe Language from the University of Education, Winneba, Ghana. Professor Kofi Gbolonyo is an internationally recognized clinician, music educator and performer. He has over 30 years of experience teaching children of all ages and professionals at different levels of education in many different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, South America, and in many states and provinces in North America.