LUNAR NEW YEAR IN A PANDEMIC

February 9, 2021

by Alice Tsui

(Please read Alice’s first post on Lunar New Year prior to reading this piece.)

In what is about to be the Year of the Ox starting on February 12th, 2021, there are still over 1 billion people around the world who celebrate Lunar New Year. Like last year, Lunar New Year is still not synonymous with Chinese New Year, as many Asian countries (but not all) celebrate this holiday. In a world changed by the pandemic since last Lunar New Year 2020, many celebrations worldwide are not in-person, but rather held digitally over Zoom, livestream events, and video calls with family. For me, Lunar New Year and its significance changes yearly. With a loss of access to visit loved ones safely due to the COVID-19 outbreak, this year Lunar New Year especially celebrates the most important aspect of the holiday - having and spending family time together.

At the onset of each Gregorian calendar year, educators will grasp at the few Lunar New Year (and predominantly Chinese based on Google searching that does not include specific countries aside from China) traditions that can be taught into the classroom, the songs with the words perceived to be “easier” to pronounce in our society, and the Pinterest-board-replicable dragons, lions, and lanterns that can adorn the real-life and online classroom. Too often, we unfortunately misuse one sole fellow educator or student we perceive to be of the culture we aim to celebrate to do the heavy lifting of educating us on what we do not know, instead of building relationships with a multitude of culture bearers who we compensate for their labor.

We must first have conversations with Asian and Asian American people and educators in our community and beyond. Lunar New Year, like any holiday or month that celebrates a specific group of people, is not meant to be treated as a checklist. In conversations with Asians and Asian Americans, share stories about your life, and listen ardently to the cultural leaders you are learning from without the automatic shift in gear we too often make into asking, “How can we bring this to our classrooms?” Simply listen, and actively reflect to understand the life-storyteller first. So often, we are asked about our Lunar New Year experiences without regard for our entire identity. As I often say as a fun fact, “I’m Asian before AND after Lunar New Year!”

As an Asian American, and specifically Chinese American music educator in Brooklyn, NYC, my celebrations consist of honoring my ancestors in a pre-Chinese New Year meal the night before. We would fold Chinese New Year paper money out of gold sheets of paper to send to our ancestors. Every dish my parents cooked had cultural significance and a recipe that was to be found nowhere but within the taste of the dish itself - only after my ancestors ate first. We would watch the Spring Festival Gala on television, filled with musical and dance performances, comedy skits, and monologues - once we were able to pay for a Chinese cable channel that showed it. Every year there would be new songs that would come out specifically for this show, some that would be “hits” and others misses. The biggest celebration would always be this dinner that simply allowed us to be together. Because Lunar New Year is not a national holiday in the United States, my mom typically worked the next day, and my brother and I would go to school. The need to survive overrode the need for celebration, even on what was the most important holiday for us each year. What I shared about my experience is only a glimpse into what occurs - not the end-all-be-all of my story nor exactly replicated each year.

From @asianlitforkids https://www.instagram.com/p/CK_wZKHnVD5/

Every year, I teach the Chinese song “Gong Xi” to my students. Although a popular song now as represented each year in Chinese New Year festivities and almost redefined by younger generations in China, I did not find out until a few years ago that this was not a popular song during my mother’s youth, and has a dark history that was never meant for celebrating Chinese New Year. While the song has taken new meaning since as one of celebration, this has been debated within different generations of Chinese culture bearers.

We must normalize that it is okay for members of an assigned cultural identity to disagree, and in this case, it is okay for fellow Chinese people to disagree with me! We are not a monolith in our identities, ideals, thoughts, or practices. For Lunar New Year, there are always many culture bearers when seeking voices to learn from, and authenticity does not always show up in a scholarly search for information. Even as I write my own experience, it is difficult to put words to Chinese traditions that I only learned about in Shanghainese and are lost in translation.

Finding out about “Gong Xi” and its debated usage came up in a random conversation with my mother during our time eating together during Lunar New Year. Our conversations that naturally include snippets of music are the ones we must hold dearly, as so often our ephemeral life commentary leads to more learning and understanding than we may give credit for. After all, for me, “everyday is Chinese New Year”.

Our understanding, regard, and care for Lunar New Year must be revisited yearly and deeply so. This Lunar New Year, it is my hope that music educators build relationships with culture bearers in order to holistically learn accurate understandings that are not clouded by the urgency of checking a performative box.

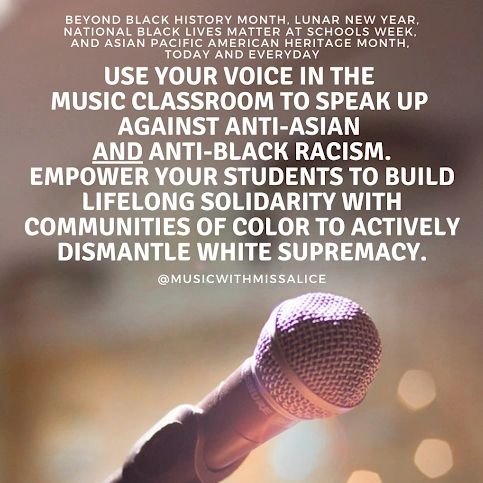

https://www.instagram.com/p/CK-SpC5hvvY/

Finally, it is my demand for us all to unite as music educators and speak up using our own platforms in life against the anti-Asian hate crimes that have occurred with our students, and to #STANDFORASIANS. We cannot only be celebrated under the pretense of being “culturally responsive”, but disregarded when the worldwide Asian diaspora is facing racial violence. The joy of celebrating Lunar New Year is inextricably linked to solidarity with Asian communities as we continue our decolonizing work in the music room.

ALICE TSUI (pronounced TSOY) is an Asian American/Chinese American pianist, music educator, and lifelong Brooklynite. She graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance and a Master of Arts in Music Education, and is currently a doctoral candidate (ABD) in music education at Boston University. Alice is the founding music teacher at P.S. 532 New Bridges Elementary, an arts-integrated public elementary school in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and is on the piano faculty at the Manhattan School of Music Summer program. As a product of the NYC public school system, Alice is passionate about anti-racist public music education and empowering the individual and collective voices of youth through music.